Spinal Stenosis Had Surgery 10 Years Ago Still Painful Can Surgery Be Done Again

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Clinical outcome subsequently surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in patients with insignificant lower extremity pain. A prospective accomplice written report from the Norwegian registry for spine surgery

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders volume xx, Commodity number:36 (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Spinal stenosis is a clinical diagnosis in which the main symptom is pain radiating to the lower extremities, or neurogenic claudication. Radiological spinal stenosis is commonly observed in the population and it is debated whether patients with no lower extremity pain should exist labelled as having spinal stenosis. Nevertheless, these patients is institute in the Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery, the main object of the present study was to compare the clinical outcomes after decompressive surgery in patients with insignificant lower extremity pain, with those with more than severe pain.

Methods

This study is based on data from the Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery (NORspine). Patients who had decompressive surgery in the menses from 7/i–2007 to 11/iii–2013 at 31 hospitals were included. The patients was divided into iv groups based on preoperative Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)-score for lower extremity pain. Patients in group 1 had insignificant pain, grouping 2 had balmy or moderate pain, group 3 severe pain and group 4 extremely severe hurting. The main event was alter in the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). Successfully treated patients were defined as patients reporting at least thirty% reduction of baseline ODI, and the number of successfully treated patients in each grouping were recorded.

Results

In total, 3181 patients were eligible; 154 patients in group 1; 753 in group 2; 1766 in group iii; and 528 in group 4. Group 1 had significantly less comeback from baseline in all the clinical scores 12 months later on surgery compared to the other groups. Withal, with a mean reduction of 8 ODI points and 56% of patients showing a reduction of at to the lowest degree 30% in their ODI score, the proportion of patients defined as successfully treated in grouping 1, was not significantly dissimilar from that of other groups.

Conclusion

This national register study shows that patients with insignificant lower extremity hurting had less improvement in principal and secondary outcome parameters from baseline to follow-up compared to patients with more severe lower extremity pain.

Background

Radicular pain in the lower extremities known as neurogenic claudication is considered to exist the main symptom of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (LSS) [i,2,3]. According to criteria from the Northward American Spine Society, the most ascendant historical and concrete finding in lumbar spinal stenosis, is gluteal or lower extremity hurting, which is exacerbated by walking and relieved past flexion of the spine [4]. Whether or not patients accept this symptom is considered one of the most of import clinical signs, when evaluating a patient for lumbar spinal stenosis [5]. Still, virtually of the patients with symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis describe both leg hurting and low dorsum pain [6], and it may be difficult for patients to ascertain whether the leg pain or back pain is dominant [7].

Depression back pain is multifactorial, and several explanations are possible. Radiological findings of lumbar spinal stenosis may be incidental, since a high proportion of radiological lumbar spinal stenosis has been documented in asymptomatic subjects [8, 9]. Dominance of leg hurting is commonly considered to exist best indication for decompressive surgery. In virtually trials the patients report postoperative improvement in functional scores, leg pain and depression back pain, after posterior decompression [ten, 11]. Some studies have tried to identify predictors of clinical outcomes afterwards posterior decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis [12], only very few stiff predictors has been institute [13]. Surgical handling for lumbar spinal stenosis is considered past many to be superior to non-surgical handling [14,fifteen,16,17], but the most contempo Cochrane review of the efficacy of surgical treatment versus non-surgical treatment, in which only trials with neurogenic claudication as main inclusion benchmark were included, did not support this determination [18]. The effect of surgery in patients with atypical symptoms and radiologically verified lumbar spinal stenosis is to our cognition not sufficiently researched.

The aim of the present written report was to investigate whether or not the degree of preoperative lower extremity hurting influences the clinical results later on decompressive surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis.

Methods

Study population

This cohort study is based on data from the Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery (NORspine). Patients labeled every bit having had surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis with midline retaining decompression in the flow from 7/1–2007 to eleven/3–2013 were included. In this period 31 of the Norwegian hospitals (86%) reported to the annals. All patients receive oral and written information amid their participation in the registry. They sign a written consent to participate in the registry. The registry protocol was approved by the Norwegian board of ethics, REC Primal (2014/98).

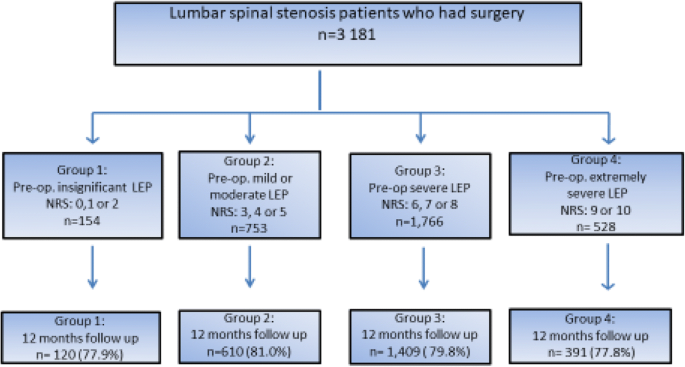

The patients in this study were divided into 4 groups based on patient-reported preoperative Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) – a score for lower extremity pain. Patients in group 1 had insignificant lower extremity hurting (NRS-score = 0, 1 and ii), group 2 had mild or moderate pain (NRS-score = 3, 4 and v), group three had severe pain (NRS-score = vi, seven and 8) and grouping 4 had farthermost severe pain (NRS-score = 9 and x) (Fig. one).

Chart showing the grouping and follow-up of patients with lumbar spinal stenosis who underwent decompression surgery; information obtained from the Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery (NORspine). LEP: Lower extremity pain

Patient reported outcome measures

The NORspine uses a recommended [19,20,21,22,23,24] set of patient reported event measures (PROMs). The questionnaires are self-administered at admission for surgery (baseline) and at 3 and 12 months follow-up. At baseline the forms also include questions about demographics and lifestyle issues.

During the hospital stay the surgeon records data concerning exact spinal diagnosis for surgery, possible spinal co-diagnosis, comorbidity, radiological classifications, the American Order of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, perioperative complications, functioning method, duration of surgery and hospital stay. Patients were selected for the present written report if the surgeon had ticked the registration form for the diagnosis lumbar spinal stenosis (without any additional spinal co-diagnosis, as degenerative spondylolisthesis) and that midline retaining decompression had been performed (without additional fusion).

Outcome cess

The primary outcome was change in hurting-related physical function, assessed past the Norwegian version of the Oswestry Inability Alphabetize (ODI) questionnaire, version 2.0 [xx]. It contains ten questions related to hurting limitations in activities of daily living, ranging from 0 (no disability) to 100 (worst possible). Successfully treated patients were defined as patients reaching at least thirty% reduction of the baseline ODI score [25], and the number of patients in each grouping reaching this level was recorded. These analyses were performed with and without adjusting for baseline values.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome measures were changes in NRS (from 0 (none) to 10 (worst possible)) for leg and back pain, and health related quality of life measured by the EQ-5D (ranging from − 0.59 to one).

The ODI, NRS pain scales, and EQ-5D have shown good validity and reliability, and the Norwegian versions of these instruments have shown good psychometric properties [22,23,24].

Statistics

Descriptive statistics for baseline characteristics were performed, besides every bit for clinical outcomes. Frequencies were used for categorical variables, whereas mean and standard deviations were used for continuous variables. To assess differences in distributions across the four patient groups, the standard Chi-foursquare test was used for chiselled variables, whereas ANOVA tests were used for continuous variables. Standard t-tests were used to analyze clinical outcomes separately for each patient grouping. Since differences in baseline parameters between the four groups were found, multivariate linear and logistic regressions were used to further analyze the association between lower extremity pain and clinical outcomes. The variables in the linear and logistic regressions were age, sex, Torso Mass Index, smoking status, preoperative ODI, preoperative NRS-score for leg pain and preoperative NRS-score for depression back pain. Age, Body Mass Index, preoperative ODI and EQ-5D were included as linear variables and smoking condition, sexual practice and the NRS-scores were chiselled variables. When analyzing the probability to be classified as successfully treated logistic regression were used, adjusting for baseline values.

Results

Baseline characteristics

There were 3181 patients with lumbar spinal stenosis who underwent decompressive surgery in this annals cohort. None of these patients had spinal co diagnosis. Regarding preoperative pain in the lower extremities, there were 154 patients in grouping 1; 753 patients in group 2; 1766 patients in group three; and 528 patients in group 4 (Fig. one).

The follow up response rate after 12 months was effectually 80% (77.eight–81.0%) (Fig. 1). Baseline information are presented in Table 1. Statistically significant differences in baseline data across the iv groups were found in all hurting and function parameters. In that location were statistically significant differences betwixt the 4 groups in age, sexual practice and in smoking, only not in BMI. Patients in group 1 were younger, and in that location were higher proportions of males and non-smokers compared to the other groups. At baseline we found that the college the NRS-score for leg pain, the college were the scores for ODI, NRS-score for low back pain, and EQ-5D (p < 0.05).

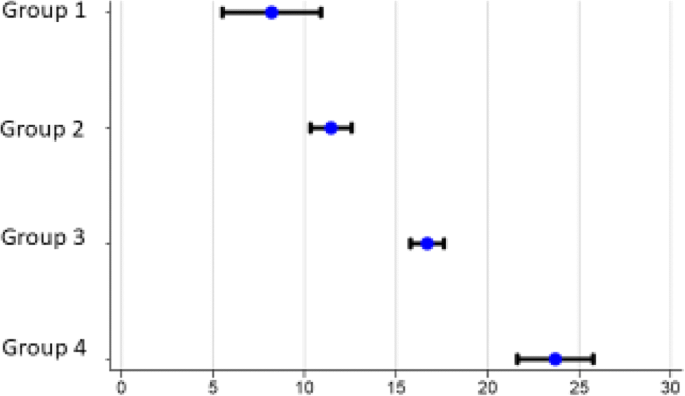

Chief effect

The mean change in ODI from baseline to 12 months postoperatively was significantly different between the four groups (Fig. 2 and Tabular array two).

Mean change in ODI score. Mean modify, decrease in ODI (with SD) from baseline to 12 months postoperative follow up. Exact values given in Tabular array 2.

The patients are divided into four groups co-ordinate to their preoperative Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) –score for lower extremity pain. Grouping 1 = NRS-score 0, 1 and 2, group 2 = NRS-score three, 4 and 5, grouping iii = NRS-score 6, 7 and viii and group 4 = NRS-score 9 and 10 for lower extremity hurting

The multivariate linear regression assay (Table iii) shows that the more intense the preoperative leg pain, the greater is the probability of achieving a positive clinical outcome measured as a numerical improvement in ODI-score. This is so fifty-fifty subsequently adjusting for factors similar age, smoking, and Body Mass Alphabetize and baseline questionnaire-scores (ODI, NRS-score lower extremity hurting, NRS-score low back hurting and EQ-5D). Groups 3 and 4 had a significantly greater improvement in the primary outcome, compared with group 1. Group 2 also appeared to take a greater comeback compared with group one, only the difference was not statistically meaning. In addition to lower extremity hurting, higher age, positive smoking status, higher BMI, high values for preoperative back pain, poor preoperative wellness condition and low preoperative ODI were factors that were associated with significantly inferior clinical outcomes (see Table 3).

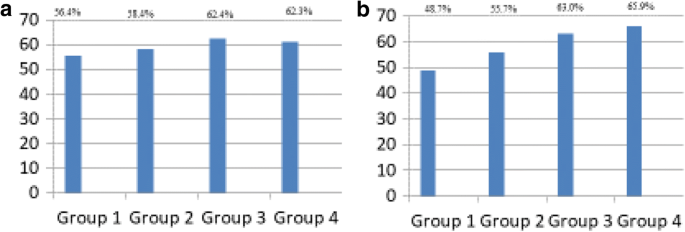

The percentage of patients classified equally being successfully treated (30% meliorate ODI than preoperatively) in each of the four groups is presented in Fig. 4. No differences were found between the four groups (Pearsons Chi-Foursquare), P = 0.19. After adjusting for differences in baseline values the predicted number of patients categorized equally successfully treated showed significantly difference between group 3 and iv versus group 1 (p = 0.01), simply not betwixt group 2 and group 1 (p = 0.23).

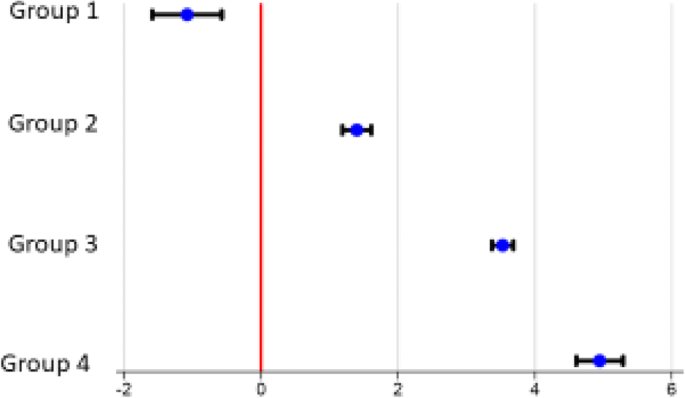

Secondary outcomes

The mean changes from baseline to 12 months follow up are given in Tabular array two. The trends for the secondary outcome parameters were the same as for the master outcome, the higher preoperatively NRS-score for leg pain, the greater the probability of a positive clinical outcome after surgery. Group 1 reported a worsening of the mean score for lower extremity pain from baseline to 12 months follow up (Table iii, Fig. 3).

Hateful change in lower extremity hurting. Mean change in lower extremity hurting (with SD) from baseline to 12 months of follow upwardly

The patients are divided into four groups according to their preoperative Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)–score for lower extremity pain. Grouping one = NRS-score 0, 1 and two, grouping two = NRS-score 3, 4 and 5, group iii = NRS-score 6, 7 and 8 and grouping 4 = NRS-score 9 and ten for lower extremity pain

Discussion

In this cohort we studied patients with lumbar spinal stenosis undergoing decompression surgery, as reported to the Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery (NORspine). Regarding the primary upshot (change in ODI), and secondary outcomes (change in EQ-5D, and NRS-score for lower extremity pain and back pain), we found a significantly lower improvement among patients with insignificant preoperative lower extremity pain, compared to the other groups with more astringent leg pain. These findings are in accordance with the findings of Kleinstuck et al. [26], who reported that more than dorsum pain than leg pain at baseline, was associated with a significantly worse outcome subsequently decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis. The multivariate linear regression analysis (Table 3) shows that the more than intense the preoperative leg pain, the greater is the probability of achieving a positive clinical event, measured as a numerical improvement in the ODI-score.

Patients with insignificant preoperative lower extremity pain reported a worsening in mean values for lower extremity hurting after surgery.

Withal, a majority of patients in the present study reported an improvement in consequence parameters, even those patients with insignificant preoperative lower extremity pain. The mean comeback was eight ODI points in this grouping, and 55.half-dozen% reported a reduction of at least thirty% in ODI score at12 months follow up (Fig. 4a).

Number of successfully treated patients in the four unlike groups. a Number of successfully treated patients in each group. Success was divers equally an improvment from baseline ODI of xxx%. No differences between the four groups were found. Pearson Chi-Square examination = 4.7755 P-value = 0.189. Analysis performed without adjusting for differnces in baseline values. b The predicted probility of being classified as successfully treated patient when adjusting for baseline variables The figure show that there are meaning differences when comparing group iii and 4 to group 1, both p-values = 0.01. Not significant values when comparing grouping ii to group one, p-value = 0.23. The patients are divided into four groups according to their preoperative Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) –score for lower extremity pain. Grouping 1 = NRS-score 0, i and two, group 2 = NRS-score 3, iv and 5, group iii = NRS-score 6, 7 and 8 and group 4 = NRS-score 9 and x for lower extremity pain

It may be argued that patients without pain radiating to the lower extremities do non fulfil the clinical criteria for spinal stenosis and should not take had surgery. Whether the improvement is due to the surgery, or a placebo effect, or the postoperative rehabilitation program, is difficult to determine. It is documented within other orthopedic fields that as well sham surgery has effect on clinical outcomes [27,28,29].

The patients in group one had significantly lower hurting- and function score at baseline compared to the other groups. They would crave less improvement to achieve a thirty% reduction of the ODI-score, compared to those loftier baseline score.. This may be part of the explanation for why the four groups show no significant difference in success rate in the unadjusted assay. Notwithstanding, when adjusting for the differences in the baseline scores, the logistic regression analysis showed significant departure between the groups in the predicted number of patients reaching a 30% improvement of ODI score. The patients with less lower extremity hurting have a statistically significant higher proportion of patients with inferior outcome compared to patients with higher degree of lower extremity pain.

Limitations of this study

In the NASS-criteria for clinical symptoms it is stated that low dorsum pain, gluteal pain and lower extremity pain are symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis.

Patients may find information technology hard to fit their symptoms into a standardized questionnaire used in a registry, so there may be errors in preoperative nomenclature. It might be difficult to place the exact location of their symptoms [six]. In the registry forms, patients are asked to quantify their hurting intensity (NRS) during the previous calendar week in the lower back or gluteal region, and in the lower extremity. Just should they for instance notation their hurting in the buttock as back hurting or leg pain? Furthermore, should buttock pain be registered as radiating hurting to the extremity?

Two of the main symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis, neurogenic claudication and relief of hurting while bending forrard, are not asked nigh, either in the patients' or in the surgeons' questionnaires. These are amongst factors that may influence the clinical event after surgery, which cannot be accounted for in the present register report. Some would claim that patients with insignificant lower extremity pain practise not accept the central symptom of lumbar spinal stenosis, and therefore should not have undergone surgery. The results of the present written report testify that the clinical outcome in patients with insignificant lower extremity pain could be interpreted as inferior. Some of these factors may account for the possibly inferior clinical outcome accounted for in patients with insignificant lower extremity pain.

Recently it has been questioned if the Oswestry Disability Index is well enough validated for patients with spinal stenosis (oral presentation in Eurospine convention 2017) [30]. However, a recent publication from the SWESPINE register show a high consistency between a five point Global Assessment-scale and the ODI questionnaire and NRS for low back pain/lower extremity pain in over 94,000 patients, including lumbar spinal stenosis patients [31]. This shows that an improvement of ODI is consistent with the patients' cocky-reported effect after surgery.

The success-rate, reported in the present study is based on success criterion of xxx% reduction from baseline ODI. There were no differences in the proportion of patients registered equally successfully treated in the four groups. This indicates that some patients take benefited from surgery. There is no consensus, to our cognition, equally to what are the best criteria for determining a successful consequence of surgery for this group of patients, and more than inquiry is needed to define optimal criteria for success [32].

The NORspine annals does not include objective radiological parameters. The patients and the surgeon can take misinterpreted the symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis. The Wakayama report from Japan [9], showed that a high proportion of an asymptomatic population had radiological findings corresponding to lumbar spinal stenosis, so the radiological findings of lumbar spinal stenosis may exist incidental findings. These factors may as well contribute to the inferior results in Group one.

This is an observational register-cohort study, and therefore reflects a variation of do amongst the Norwegian surgeons performing spinal surgery. Information about multiple patient-related factors that influence the decision making of the surgeon is not always possible to incorporate in a registry. To answer specific questions, 1 needs to perform a prospective comparative trial, preferably a randomized trial.

Strengths of this trial

A register trial has a high external validity. This is a cohort from most of the hospitals performing spinal surgery in Kingdom of norway in the given menses. The high numbers of patients in the study strengthens the validity of the results.

The surgical techniques used in this report are similar, and have been documented not to influence the clinical result. All patients in the present study had surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis with spinal decompression with a midline retaining method (unilateral laminotomy with crossover, bilateral laminotomy or spinous process osteotomy), without additional fusion. A previous study from the aforementioned register showed like clinical results after using these 3 posterior decompression techniques [10].

Conclusion

In this national register study the analysis show that patients with insignificant lower extremity pain had less improvement in main and secondary consequence parameters from baseline to follow-up compared to patients with more than astringent lower extremity pain.

References

-

Amundsen T, Weber H, Lilleas F, Nordal HJ, Abdelnoor M, Magnaes B. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Clinical and radiologic features. Spine. 1995;20(10):1178–86.

-

Katz JN, Dalgas M, Stucki G, Katz NP, Bayley J, Fossel AH, Chang LC, Lipson SJ. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Diagnostic value of the history and physical examination. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(ix):1236–41.

-

Postacchini F. Surgical direction of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24(10):1043–vii.

-

Kreiner DS, Shaffer WO, Baisden JL, Gilbert TJ, Summers JT, Toton JF, Hwang SW, Mendel RC, Reitman CA, N American Spine S. An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis (update). Spine J. 2013;13(7):734–43.

-

Tomkins-Lane C, Melloh M, Lurie J, Smuck Thousand, Battie MC, Freeman B, Samartzis D, Hu R, Barz T, Stuber K, et al. ISSLS prize winner: consensus on the clinical diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis: results of an international Delphi study. Spine. 2016;41(fifteen):1239–46.

-

Watters WC III, Baisden J, Gilbert TJ, Kreiner S, Resnick DK, Bono CM, Ghiselli G, Heggeness MH, Mazanec DJ, O'Neill C, et al. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: an show-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and handling of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine J. 2008;8(two):305–10.

-

Wai EK, Howse K, Pollock JW, Dornan H, Vexler 50, Dagenais S. The reliability of determining "leg dominant pain". Spine J. 2009;nine(6):447–53.

-

Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. JBone Articulation SurgAm. 1990;72(3):403–eight.

-

Ishimoto Y, Yoshimura N, Muraki Due south, Yamada H, Nagata 1000, Hashizume H, Takiguchi N, Minamide A, Oka H, Kawaguchi H, et al. Associations between radiographic lumbar spinal stenosis and clinical symptoms in the general population: the Wakayama spine written report. OsteoarthritisCartilage. 2013;21(6):783–eight.

-

Hermansen E, Romild Uk, Austevoll IM, Solberg T, Storheim One thousand, Brox JI, Hellum C, Indrekvam K. Does surgical technique influence clinical effect after lumbar spinal stenosis decompression? A comparative effectiveness study from the Norwegian registry for spine surgery. Eur Spine J. 2016.

-

Jones AD, Wafai AM, Easterbrook AL. Improvement in low dorsum pain following spinal decompression: observational written report of 119 patients. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(1):135–41.

-

Nerland US, Jakola As, Giannadakis C, Solheim O, Weber C, Nygaard OP, Solberg TK, Gulati S. The adventure of getting worse: predictors of deterioration afterward decompressive surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a multicenter observational study. Globe neurosurgery. 2015;84(4):1095–102.

-

Turner JA, Ersek M, Herron L, Deyo R. Surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. Attempted meta-analysis of the literature. Spine. 1992;17(one):one–viii.

-

Amundsen T, Weber H, Nordal HJ, Magnaes B, Abdelnoor Thousand, Lilleas F. Lumbar spinal stenosis: conservative or surgical management?: a prospective 10-twelvemonth study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(eleven):1424–35.

-

Jacobs WC, Rubinstein SM, Willems PC, Moojen WA, Pellise F, Oner CF, Peul WC, van Tulder MW. The show on surgical interventions for low back disorders, an overview of systematic reviews. EurSpine J. 2013;22(9):1936–49.

-

Malmivaara A, Slatis P, Heliovaara G, Sainio P, Kinnunen H, Kankare J, In-Hirvonen N, Seitsalo Due south, Herno A, Kortekangas P, et al. Surgical or nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis? A randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(1):ane–viii.

-

Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Tosteson A, Blood E, Herkowitz H, Cammisa F, Albert T, Boden SD, Hilibrand A, et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis four-year results of the spine patient outcomes research trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(xiv):1329–38.

-

Zaina F, Tomkins-Lane C, Carragee Eastward, Negrini South. Surgical versus nonsurgical handling for lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2016;41(14):E857–68.

-

Clement RC, Welander A, Stowell C, Cha TD, Chen JL, Davies M, Fairbank JC, Foley KT, Gehrchen M, Hagg O, et al. A proposed set of metrics for standardized outcome reporting in the direction of low back pain. Acta Orthop. 2015;86(5):523–33.

-

Fairbank JC, Pynsent Lead. The Oswestry disability alphabetize. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(22):2940–52.

-

Ferreira-Valente MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Hurting. 2011.

-

Nord E. EuroQol: health-related quality of life measurement. Valuations of health states by the general public in Norway. Health Policy. 1991;xviii(i):25–36.

-

Rabin R, de CF. EQ-5D: a measure of health condition from the EuroQol grouping. AnnMed. 2001;33(5):337–43.

-

Solberg TK, Olsen JA, Ingebrigtsen T, Hofoss D, Nygaard OP. Wellness-related quality of life assessment past the EuroQol-5D can provide toll-utility information in the field of low-back surgery. EurSpine J. 2005;xiv(10):yard–7.

-

Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Kerns RD, Ader DN, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;nine(2):105–21.

-

Kleinstuck FS, Grob D, Lattig F, Bartanusz V, Porchet F, Jeszenszky D, O'Riordan D, Mannion AF. The influence of preoperative back pain on the result of lumbar decompression surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(11):1198–203.

-

Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, Wark JD, Mitchell P, Wriedt C, Graves S, Staples MP, Murphy B. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(half dozen):557–68.

-

Schroder CP, Skare O, Reikeras O, Mowinckel P, Brox JI. Sham surgery versus labral repair or biceps tenodesis for type II SLAP lesions of the shoulder: a 3-armed randomised clinical trial. Br J Sports Med. 2017.

-

Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itala A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, Kalske J, Ikonen A, Jarvela T, Jarvinen TA, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus placebo surgery for a degenerative meniscus tear: a 2-year follow-upwards of the randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017.

-

Wertli MMR. Validity of lumbar spinal stenosis issue measures used in clinical studies: a systematic assay of randomized and observational clinical trials. In: Orally presentation in Eurospine convention 2017 Dublin; 2017.

-

Parai C, Hagg O, Lind B, Brisby H. The value of patient global assessment in lumbar spine surgery: an evaluation based on more than 90,000 patients. Eur Spine J. 2017.

-

Copay AG, Martin MM, Subach BR, Carreon LY, Glassman SD, Schuler TC, Berven South. Assessment of spine surgery outcomes: inconsistency of modify among effect measurements. Spine J. 2010;10(4):291–6.

Acknowledgements

Cheers to Paul Saunderson, Md for linguistic assistance in writing the manuscript.

Funding

This trial accept, received funding from Western Norway Regional Wellness Say-so (RHA).

Availability of information and materials

All datasets that the conclusion is based upon is referred in the manuscript text. The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

EH, TÅM, IMA, FR, TS, KS, OG, JA, JIB, CH, KI have been involved in drafting. the study. All authors read and canonical the final manuscript. All authors meet the ICMJE guidelines for authorship.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics blessing and consent to participate

All patients receive oral and written information amid their participation in the registry. They sign a written consent to participate in the registry. The registry protocol was approved by the Norwegian board of ethics, REC Cardinal (2014/98).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None of the authors accept any competing interests.

Publisher'southward Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and point if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this commodity

Hermansen, Due east., Myklebust, T.Å., Austevoll, I.K. et al. Clinical outcome after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in patients with insignificant lower extremity pain. A prospective accomplice report from the Norwegian registry for spine surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 20, 36 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2407-5

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2407-5

Keywords

- Lumbar spinal stenosis

- Lower extremity hurting

- Annals trial

- Clinical outcome

Source: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-019-2407-5